Aeronautics Essentials: What is it?

Aeronautics (aeronautics – from the Greek aer – air and nauta (Greek ναυτα – floating, seafaring) – vertical and horizontal movement in the Earth’s atmosphere by lighter-than-air aircraft (as opposed to aviation, which uses heavier-than-air aircraft).

Until the early 1920s, the term “aeronautics” was used to refer to movement by air in general.

History of Aeronautics

The idea of taking to the air, of taking advantage of the vast ocean of air as a means of communication, is very old. Since ancient times there have been attempts, though mostly in vain.

The Invention Of Joseph Mongolfier

“Quickly prepare more silk cloth, ropes, and you will see one of the most amazing things in the world,” was the note Etienne Mongolfier, owner of a paper mill in a small French town, received in 1782 from his older brother Joseph. The message meant that at last they had found what the brothers had repeatedly talked about during their meetings: the means by which one could take to the air. This remedy turned out to be a smoke-filled shell. As a result of a simple experiment, J. Mongolfier saw how a cloth shell, sewn in the shape of a box from two pieces of cloth, after filling it with smoke rushed upwards.

Joseph’s discovery also fascinated his brother. Now working together, they built two more aerostatic machines (as they called their balloons). One of them, made in the form of a balloon with a diameter of 3.5 meters, was demonstrated in the circle of relatives and friends. It was a complete success – the shell stayed in the air for about 10 minutes, thus rising to a height of nearly 300 meters and flying through the air about a kilometer. Inspired by their success, the brothers decided to show the invention to the public.

They built a huge balloon with a diameter of more than 10 meters. Its shell, made of canvas, was reinforced with a rope net and lined with paper to increase impermeability. The demonstration of the balloon took place in the market square of the city on June 5, 1783 in the presence of a large number of spectators. The balloon, filled with smoke, flew upward. A special protocol bearing the signatures of the officials witnessed all the details of the experience.

This was the first official verification of the invention that opened the way to aeronautics.

PROFESSOR CHARLES’ INVENTION

The Montgolfier brothers’ balloon flight aroused great interest in Paris. The Academy of Sciences invited them to repeat their experience in the capital. At the same time, the young French physicist Professor Jacques Charles was ordered to prepare and conduct a demonstration of his flying machine.

Charles was convinced that Mongolfier’s gas, as smoky air was then called, was not the best means for creating aerostatic lift. He was well acquainted with the latest discoveries in chemistry and believed that the use of hydrogen, as it was lighter than air, offered far greater advantages. But having chosen hydrogen to fill the airframe, Charles was faced with a number of technical problems.

The first problem was how to make a lightweight shell that could hold the volatile gas for a long time. On August 27, 1783 Charles’s flying machine took off on the Champ de Mars in Paris. In front of 300 thousand spectators, it soared upwards and soon became invisible.

When someone in the audience exclaimed: “What’s the point of all this?” – Benjamin Franklin, a famous American scientist and statesman in the audience, remarked, “What’s the point of a newborn baby coming into the world?” The remark proved prophetic. A “newborn” was born with a great future ahead of it.

THE FIRST AIR PASSENGERS.

The successful flight of Charles’s balloon did not stop the Montgolfier brothers in their intention to take up the offer of the Academy of Sciences and demonstrate in Paris a balloon of their own design. Etienne used all his talents to make the greatest impression, and it is not without reason that he was also considered an excellent architect.

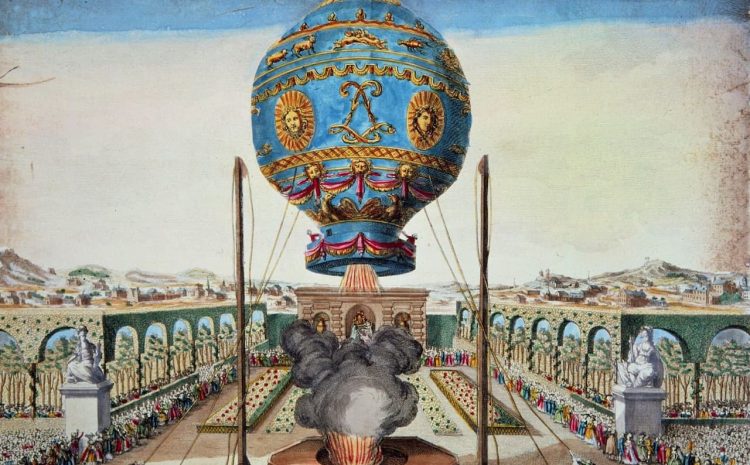

The balloon he built was in a sense a work of art. Its shell, more than 20 meters high, had an unusual barrel shape and was decorated on the outside with monograms and colorful ornaments. The balloon was admired by the officials of the Academy of Sciences and it was decided to repeat the demonstration in the presence of the Royal Court.

The demonstration took place in Versailles (near Paris) on 19 September 1783. However, the balloon which delighted French academics did not survive to this day: its shell was washed away by rain and became unusable. But this did not stop the Montgolfier brothers.

Working day and night, they built by the deadline a ball that was as beautiful as its predecessor. To make the effect even greater, the brothers attached a cage to the balloon and put a sheep, a duck and a rooster. They were the first passengers in the history of ballooning. The balloon took off from the platform and soared upward, and in eight minutes, after traveling four kilometers, it safely descended to earth.

The Montgolfier brothers became the heroes of the day, were awarded prizes, and all balloons in which smoke air was used to create lifting power, became known as Montgolfiers from that day on.

FROM DREAM TO PROFESSION

Attempts to realize controlled ballooning in France in the early years of aeronautical development did not yield positive results. And the interest of the general public in demonstration flights gradually turned aeronautics into a special kind of spectacular events.

But in 1793, that is, ten years after the first human flights in balloons, the scope of their practical application was discovered. The French physicist Guiton de Morveau proposed the use of tethered balloons to lift observers into the air.

The idea came at a time when the enemies of the French Revolution were trying to strangle it. The technical design of the tethered aerostat was entrusted to the physicist Coutelle. He succeeded in his task and in October 1793 the balloon was sent to the army in force for field tests, and in April 1794 a decree on the organization of the first aeronautical company of the French army was issued.

Coutelle was appointed its commander. The appearance of tethered balloons over the positions of French troops stunned the enemy: rising to a height of 500 meters, the observers could see far into the depths of his defense. Intelligence data was transmitted to the ground in special boxes, which descended on a string attached to the gondola. After the victory of the French troops, the National Aeronautical School was established by a decision of the Convention.

Although it lasted only five years, the beginning was made: ballooning became a profession.